Professor, University of Tsukuba Hospital

Director of the General Clinical Education Center, University of Tsukuba Hospital

Female Physician Career Support Coordinator

Emiko Seo

Graduated from the School of Medicine at the University of Tsukuba. Obtained a PhD from the Graduate School of Comprehensive Human Sciences at the University of Tsukuba. Specializes in gastroenterology. Since 2004, has been engaged in medical education, including clinical training, at the Tsukuba University Hospital General Clinical Education Center. Since 2007, has also worked as a career support coordinator for female doctors, and currently provides career counseling not only within the hospital but also to female doctors working in Ibaraki Prefecture and doctors in the regional quota system.

As the shortage of doctors continues, work style reforms for doctors have begun, making it essential for each medical institution to create an environment where doctors can work comfortably. We spoke to Emiko Seo, Director of the Comprehensive Clinical Education Center, about the system launched in 2007 at the University of Tsukuba Hospital that focuses on making it easier for female doctors to work and supporting their career advancement.

Our hospital began working to support the career advancement of female doctors after being selected as a Good Practice by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (a program to promote the training of high-quality medical professionals in response to social needs). The reason behind this was that Ibaraki Prefecture was suffering from a chronic shortage of doctors. As we increased the number of doctors, we aimed to become a hospital and prefecture that female doctors would choose to work at.

The reason we initially targeted female doctors was because the ratio of female students at the School of Medicine, University of Tsukuba was already high. When I enrolled in 1989, most medical schools had a female student ratio in the 10% range, but at our school, female students accounted for 30-40%. However, there are many difficulties and hardships that come with staying at a university hospital and obtaining specialist qualifications. Therefore, we decided to build a system that not only makes it easier for female doctors to work, but also focuses on career advancement and supports female doctors who have high abilities and ambition. I believe this innovative approach was recognized.

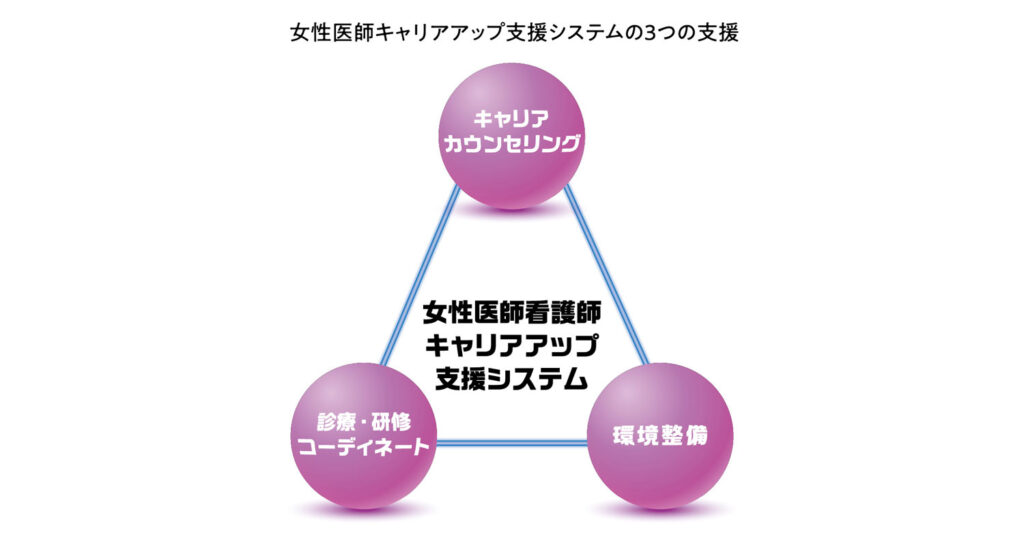

The General Clinical Education Center, where I work, has been playing a central role in building and running a support system. Because many female doctors are forced to give up on career advancement due to pregnancy, childbirth, and childcare, we have established three pillars of support: (1) medical treatment and training coordination, (2) career counseling, and (3) environmental improvement, and we organically link these to support the career advancement of female doctors (see diagram).

The majority of female doctors who receive career advancement support are referred by their departments. Approximately 15 to 20 people register each year, with 18 registered this fiscal year (2024).

All registered members must first meet with a career coordinator. During the interview, they will discuss the individual's career goals and plans, as well as their family structure, childcare support environment, and partner's working situation. They will then discuss with their department how many hours they will work per week and what kind of medical treatment and training they will receive, and then put this into a specific weekly schedule. If they try working under this plan and find it difficult to balance it, the career coordinator will adjust the plan as needed, coordinating with the individual and their department.

This flexibility is possible because we have established a short-time work system, we employ female doctors in a separate category (return-to-work support category) from full-time employees, and we also differentiate in terms of treatment. We believe this is an important point in allowing fellow doctors to work comfortably and avoiding divisions between doctors.

At the same time, creating an environment that supports balancing work and childcare is also necessary. Our hospital's sick child daycare center does not have full-time childcare staff. Instead, a sitter is on call for two hours each morning. However, the contract ends if there are no users after that time. This makes it easier to respond to morning calls from users and keeps operating costs low. This type of sick child daycare center is known within the prefecture as the "Tsukuba Method," and is spreading to other hospitals. Furthermore, cooperation from the pediatrics department is essential for the operation of the sick child daycare center. At our hospital's sick child daycare center, the pediatrician makes rounds to monitor the condition of sick children. Now, the sick child daycare center is available to nurses, pharmacists, and other hospital staff, as well as male doctors.

Approximately 80% of the female doctors we have supported over the past 18 years have transitioned to full-time work after working part-time. While the results from a medical management perspective are unclear, we believe the system has been able to continue over the long term because it has created a certain level of satisfaction within hospitals and departments. The same can be said for the female doctors who use it, and we believe that a trend has emerged where they have introduced the support system to their junior colleagues because they felt it was a good idea for them to use it. We also believe that a key to its success is that it is positioned not simply as childcare support, but as temporary support to help female doctors get through the most difficult period in their lives.

We live in an age where men are encouraged to take childcare leave, and some male doctors are considering working part-time while raising their children. Going forward, we feel strongly that it is necessary to expand this career advancement support system to include male doctors as well, and to create a work system that allows both men and women to choose from a variety of work styles. This will also make a significant contribution to securing doctors in Ibaraki Prefecture.

Because this is now an unavoidable issue, I believe that each medical institution is considering and introducing various child-rearing support measures and working to create an environment in which female and young doctors can continue working. However, there are many female and young doctors who are unaware of this. Rather than doing this quietly within the hospital so that doctors who are raising children will think, "I want to work at that hospital," it is important to publicize this as a support system and promote it to the local community.

▼Sexuality physician career advancement support system

https://www.hosp.tsukuba.ac.jp/iryojinGP/iryoGP2/program/index.html